This article was written by XSeed Partner, Robert Siegel, and appeared in the Industrialist’s Dilemma.

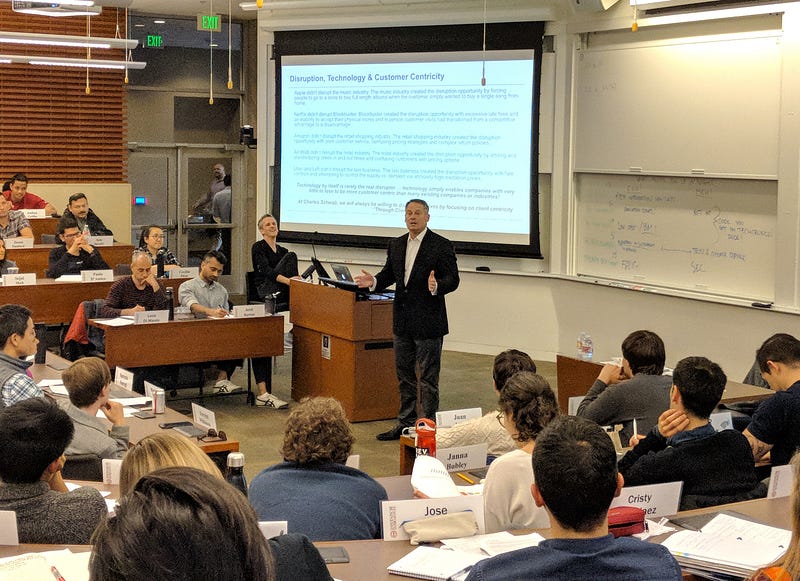

As we ended our third year of teaching The Industrialist’s Dilemma, we finished the course with Walt Bettinger, CEO of Charles Schwab, as our guest. With over $3.3 trillion currently under management (about the same value of the national assets of Switzerland and Taiwan), Schwab started as a disruptor in the FinTech space when it was established by Chuck Schwab (GSB ’61) in 1975. And while the company still talks about itself as an upstart and underdog, the corporation has become a formidable force in the financial services sector as it continues to take share from others by adding billions of dollars of net new assets under management at an increasing rate each month.

Bettinger helped reinforce certain themes that have come up over the history of our course, as well as some new ones that became more prevalent this year. One particular item which he echoed and that we saw all year: The incumbents are awake and are ready to fight for their turf.

When Size and Incumbency Work for You

One of the key issues that came up during this class was the idea that Schwab is facing battles on two fronts — from the old-line “wire houses” such as Goldman Sachs, JP Morgan, etc., for those customers who desire a higher-touch relationship, and also from the new digital upstarts such as Robin Hood and their ilk at the low-end. Students raised the concern that Schwab was being forced to fight a two-front war and might end up being mediocre at serving both segments.

Bettinger tried to re-frame the students’ thinking in a different way; he pointed out that the size and scale of Schwab’s current business, and the history of coming from a low-cost operating philosophy that goes back to the company’ beginning, allows Schwab to operate at a greater efficiency than their high-end competitors. This advantage allows the company to offer basically the same or better services with a cost basis that is more than 2/3 lower than the wire houses. As such, Schwab can compete with a high quality of service and a very cost effective operating foundation such that customers don’t ever have to compromise on either cost or quality.

Bettinger pointed out that many individuals have realized that they can’t “beat the market” on a consistent basis, and thus there has been a tremendous flow of capital into ETFs. Once these assets are created (by Schwab or others), his company is able to operate its business at a substantively lower cost than their competition while still maintaining incredibly high operating margins. These savings get passed on to customers, who can thus conduct transactions at lower prices than with other “full service” financial firms. And Schwab can afford to pass along these savings to its customers because of its low cost basis.

At the lower end of its business, Bettinger pointed out Schwab is already offering cost effective services, but with a profitable foundation. As his company’s clients increase the amount of assets they keep at Schwab, individuals get access to other financial services through Schwab at both low-cost and also a high quality touch. Does Schwab offer every service for free? No. But Schwab customers get great support, a wide variety of services and at a reasonable price.

And by being (extremely) profitable, customers know that Schwab will be around for the long-term. Bettinger argues that this is an important consideration for people when they are managing their retirement funds, which gets us to our second major takeaway from his session…

Is Every Generation Really That Different?

A consistent theme that comes up in our class, from mobility to healthcare to hospitality to financial services, is that there is a conventional wisdom that the younger generation (read Millennials) are radically different than every prior generation, and everything the younger generation wants from the companies with which they do business will be a radical departure from the past.

Bettinger echoed a theme that we also heard from Logan Green of Lyft — while some of the ways in which the younger generation will interact with companies will be different (more digital, more mobile, etc.), many of the underlying needs of customers are consistent across generations. Young families need mobility that can carry a whole family at one time — and they will want a vehicle that may reflect the life (and mess) of young children. While who own those vehicles and how these vehicles are maintained and serviced might change from the past, moving around two children and a dog has some strong commonality today to doing the same thing thirty years ago.

Similarly, as people gain additional assets as their careers advance and as they get older, they want to know that their retirement money is safe, growing and flexible where needed. As such, as long as Schwab offers compelling tools and ways to interact with its customers (including voice, new digital platforms, etc.), the desire for stability and risk will likely stay consistent with people as they age, much as it has for hundreds of years.

When you start to make meaningful money, your desire to make overly risky decisions changes. You will want to work with organizations that are safe, that will be there for you, and that won’t take risks with your money. –@WaltBettinger, CEO of @CharlesSchwab #IndusDilemma

— Stanford Business (@StanfordGSB) March 20, 2018

The Giants Are Awake

If there were two over-arching themes that we saw this year, they would be the following:

- While the disruptors are continuing to innovate, the establishment we studied is aggressively working to confront these digital battles in creative ways, and they are using their size and resources to their advantage. While many of the larger firms we saw are at various stages in their digital transformation, and all are wrestling with legacy challenges that must be dealt with in parallel to their digital innovation efforts, all of our incumbent guests were extremely cogent in describing their activities, awareness of the competition, and having an opinion on customer desires. And they discussed, at various levels of conviction, the ways that they are changing their organizations and product development routines. The incumbents seem well aware of the challenges that they are confronting.

- It takes longer than Silicon Valley thinks. When we started exploring this space three years ago, conventional wisdom was that only those incumbents who speedily changed their product development behaviors and organizations would avoid being rapidly left behind by the new disruptors that were remaking the world in their image. Three years later we are beginning to see the second round of battles beginning between upstarts and incumbents. The incumbents are awake and moving — the disruptors have woken the sleeping giants across the board. And now we are starting to observe the second stage of engagements take shape, which appear to revolve around the reorganizing of value chains, the development of new partnerships, and some extremely intense forthcoming conflicts around customer ownership. These industrial markets take longer to change than others may have anticipated, and that has given the incumbents the ability to respond.

We’ve seen the first punches and counterpunches. Now the hard part is truly beginning for parties on both sides.

The teaching team is looking forward to our next iteration of learnings when we continue The Industrialist’s Dilemma in the next academic year. For now, we go back to our interviews and case writing to learn more about these evolving landscapes and ways of doing business.