This article was written by XSeed Partner Robert Siegel and appeared in the Systems Leadership section of casasiegel.com.

We finished this year’s Systems Leadership course with Tony Thomas, CIO of Nissan. The class session entailed a rich discussion of how Systems Leaders need to drive transformational change during uncertain times. Thomas joined Nissan eight months ago, after having extensive tenures at GE, Vodafone and Citi. He entered Nissan as the mobility industry is going thru extensive changes the likes of which have not been seen in the last 100 years.

Nissan faces its own unique situation in this industry — it is a member of the Alliance with sister organizations Renault and Mitsubishi, and the company sells high-end performance vehicles, luxury sedans and trucks all over the world. In addition, the company has a rich legacy with their Japanese culture and its associated strengths, while it is at the same time confronting changing customer demands, channel disruption and the rise of new entrants into the mobility market. Thomas shared the specific challenges in his role as a relative newcomer to both the industry and company, as he works to bring his experiences in digital transformations that have affected other well-regarded and well-established organizations.

It Starts with Being a Leader

Perhaps the most difficult challenge for a Systems Leader is not just to successfully navigate through the previously covered topics in our blog posts, but to do so during times of great uncertainty. When so many things are changing — markets, customers, technologies — perhaps the greatest battle for Systems Leaders occurs inside the minds of those who must lead either an incumbent or an emerging company into the competitive vortex when there is very little likelihood that outcomes will turn out as planned.

While a Systems Leader must manage organizations, channels, products and fellow travelers, the greatest challenge might come in managing one’s self. How one navigates through crises, business cycles and the extreme ups and downs of market disruptions where no roadmaps exist might be the hardest thing for a leader to confront.

But when “playing for a win” and doing so in extremely ambiguous times, how does one know when leaders are making smart, aggressive moves or enacting foolish decisions? Even some of the best-known business leaders are questioned at various points — was Elon Musk brilliant for the introduction of the Model 3, or did he over-extend himself?

For Thomas, joining Nissan forced him to understand not only the dynamics of the mobility market, but also the operations of the organization in which he must function. He had to quickly change the mindset of his team from thinking as a cost function to having the mindset of being a revenue generator — and to do so on a global basis for the company. With data being the key enabler to delivering better products and services, Thomas is working to transform the thinking in his group to seek how to gather more information that drives better customer outcomes, but to do so in a way that is open and transparent to all.

And he must do these things when it is very unclear how the mobility market will transform and what will be the results of his activities.

It Starts with the Person in the Mirror

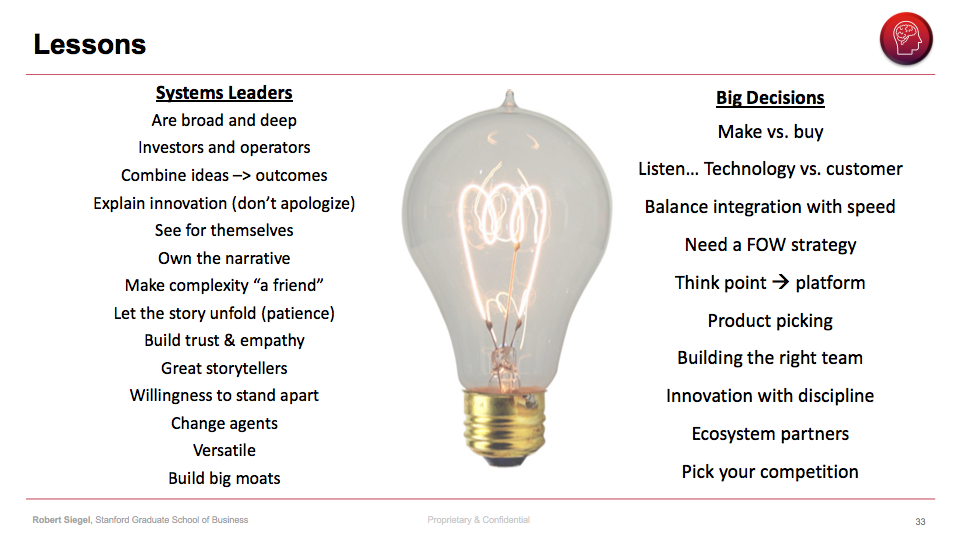

When talking to the variety of leaders we hosted, all of whom are experiencing the digital industrial transformation firsthand, each one mentioned the importance of several key issues that help them navigate through the most volatile and opaque moments each faces as a Systems Leader. While some of these takeaways seem broadly applicable across any organization going through extreme volatility, Thomas and others stressed some that are unique to this particular transformation:

1) Patience — Most leaders have the natural instinct to take action in order to drive outcomes. However, leaders must balance this natural bias to be a driver of change with the notion of ensuring that one has gathered enough data to see how “the story is playing out” over the short- and medium-term. One of the key attributes Systems Leaders need to internalize is how they can gain insights by gathering primary data — by taking the time to learn what is happening as they spend time in the field with customers, in factories with workers and in the labs with engineers to understand how the proverbial chess pieces are being moved across the chess board. Industrial markets do not go up and down with the speed of consumer products or video games; they take time to evolve and change. Patience can be a virtue, which often goes against the natural instincts of leaders who are trained and wired for action.

2) Compartmentalization — With the magnitude of volatility that comes from businesses that are facing changes that might only occur every 50 or 100 years, it can seem that Systems Leaders face new existential crises every week and from multiple areas. A key skill of Systems Leaders is to compartmentalize each of the seemingly endless eruptions that appear to come on top of each other with constant and increasing frequency. Whether each of these challenges are independent or are linked by the upheaval that Systems Leaders are confronting, executives need to adhere to the adage that, “Leadership is the ability to constrain a response to a given stimulus.” The capability to make sense and order out of noise, and not to allow each new unplanned challenge to create a series of layers that prevent clarity in one’s ability to think clearly, can only be achieved when Systems Leaders compartmentalize each new event and place it in context to the larger changes going on with a business.

3) Learn from Failures — As organizations attempt new and innovative projects, products and activities, some will inevitably fail. The Systems Leader has two key tasks when actions are not going as planned: knowing when to stop a project and also how to learn from a given failure. On the former, when key metrics and milestones are not achieved it is often critical to “cut bait” and move on. Systems Leaders in large companies can look to best practices in the startup world and venture capital on how to manage these situations — when key milestones are not achieved, future rounds of funding usually do not follow for startup companies. Systems Leaders need to enforce this same discipline inside of their organizations and not throw “good money after bad.” While innovation is often difficult and takes a long time, when a key metric for customer success is consistently missed and not achieved, killing a project is often the best step that a leader can take.

A second valuable tool is ensuring that one gets an external perspective on a failure. These outside points of view can come from trusted customers, advisors or partners, and Systems Leaders must receive insights and input from those who are not caught up in the “tyranny of the urgent” that can arise from being inside of an organization. Allowing trusted parties to provide broader perspectives on why something failed can be a valuable tool for learning why projects did not succeed and can enable an organization not to make a similar mistake in future endeavors.

Key lessons from the class sessions.

4) Act and Listen at the Same Time — As discussed previously, Systems Leaders need to manage at intersections: large and small, fast and slow, etc. In the same way, Systems Leaders also need to develop the ability both to act and to listen simultaneously. By acting, Systems Leaders must deploy resources in key and emerging areas and must give clear and concise messages about the direction of the company. At the same time, Systems Leaders must also clearly show what paths the company will abandon and the reason for such a decision. The broader organization looks to Systems Leaders for direction that is delivered with clarity and unambiguousness.

And, yet, Systems Leaders must also simultaneously be listening in order to understand what is working and what is not inside of a company. This listening can be either to trusted outside parties or to insightful internal individuals, but Systems Leaders must figure out how to manage at the intersection of talking (leading) and listening (learning) — especially in those moments when times are most unclear.

5) Know the Difference Between Skill and Luck — One of the most prevalent leadership challenges for any individual is to understand the difference between skill and luck. A great Systems Leader needs to be aware of what variables he/she and his/her company are able to control, and what challenges are part of a normal business cycle over which they have no influence. Being intellectually honest on how one’s actions and behaviors shape an outcome, and how one may simply be “in the right place at the right time” (or the “wrong place at the wrong time”) will help a leader understand what actions to take in times of uncertainty that might lead to a positive outcome, and how previous actions might have only worked contextually given broader market forces.

6) Leader Know Thyself — Acting as a Systems Leader in a company undergoing frame-breaking change requires a combination of self-confidence, self-awareness and the capability for self-improvement. This cycle of the digital industrial transformation demands the ability for self-reflection, self-criticism, and finally, self-renewal. Systems Leaders must survive and grow through times of extreme volatility. Being aware of one’s own strengths and development needs is a key tool for knowing if one can successfully guide an organization through a time of unparalleled volatility — like the one Systems Leaders are going through right now during the digital industrial transformation.