This article was written by XSeed Partner Robert Siegel and appeared in the Systems Leadership section of casasiegel.com

The complexity facing the United States healthcare market is staggering. With the percentage of healthcare spending approaching 20% of the United States’ GDP, the importance of this issue is existential both socioeconomically for the country, as well as personally for every individual.[1] For healthcare providers, the ability to stay focused on serving patients is oftentimes overwhelmed by the interactions that their organizations must manage with physicians, employees, insurers, technology providers, and in the case of UCSF Health, the city and communities in which they operate.

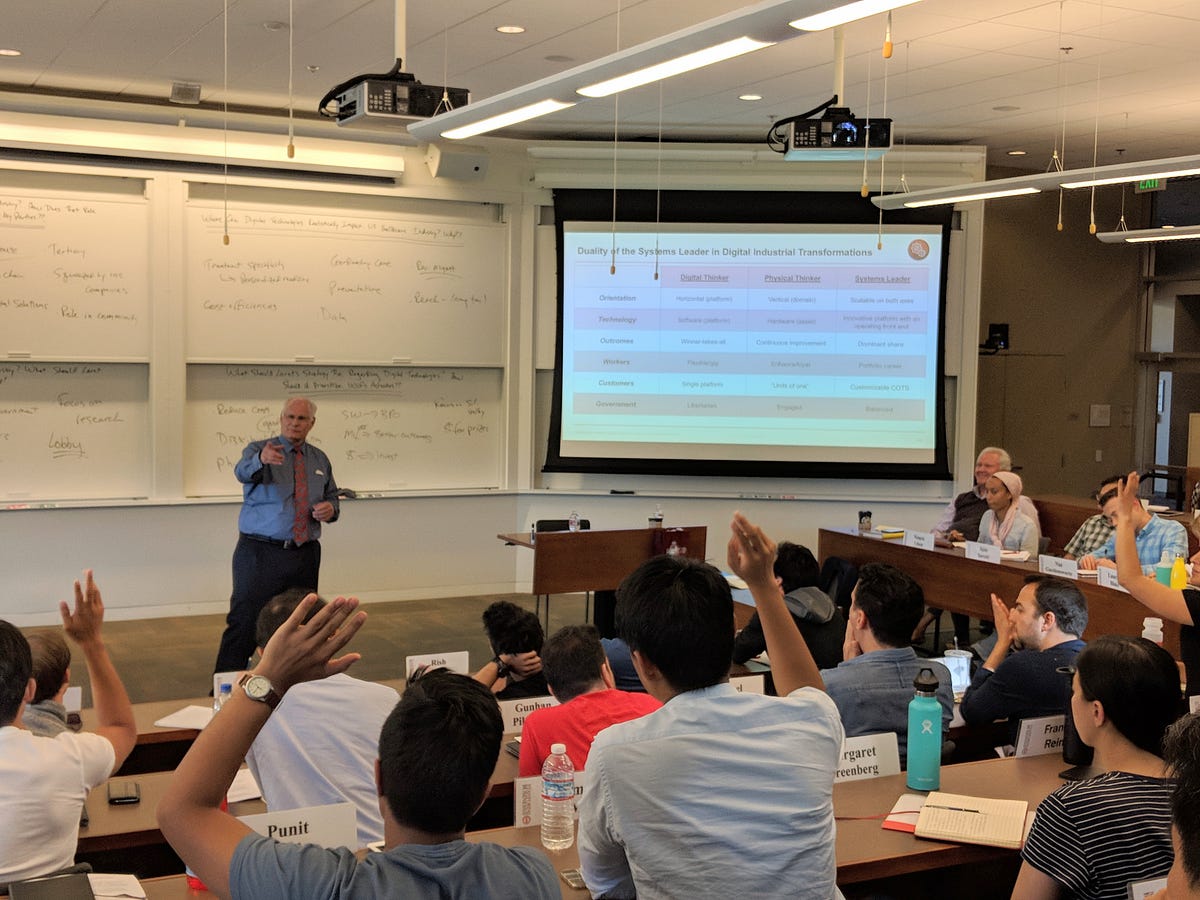

Mark Laret, CEO of UCSF Health, displayed the versatility and clear-thinking required of a Systems Leader who runs one of the top five hospitals in the country, and one that also happens to be one of the leading medical research institutions in the world while being a campus in the University of California education system. How Laret and his team have to organize and operate within an overly complex ecosystem was the topic of our seventh class session.

Develop an Influence Map

Develop an Influence Map

As digital industrial companies engage with customers, competitors and fellow travelers, it becomes quickly apparent that markets tend to be extremely complicated when technologies, customers and the skillsets required for success are rapidly changing. Systems Leaders need to constantly think about who in the broader ecosystem is a friend and who is an enemy of their company. Those firms that sell products which directly compete against one’s own are perhaps the easiest to categorize and deal with — they are the enemy, and a Systems Leader’s job is to beat them when selling to a customer.

But aside from direct competitors, how can one know which other firms are friends and which are enemies? Sometimes partners evolve into competitors; the phrase “coopetition” is often credited to Ray Noorda from the early 1990s when he was the CEO of Novell. Noorda described those paradoxical situations where companies sometimes need to cooperate with each other, and other times when they need to compete against each other.[2]

At a moment when companies increasingly must coordinate together in order to deliver complete solutions to customers, it is often not easy to tell the difference between who is actually a partner and who is a competitor looking to marginalize one’s organization. One tool that leaders can use which helps provide some insights on these situations is an influence map of an industry. This tool allows leaders to see what parts of an ecosystem are driving others, and the magnitude of these influences.[3] Key attributes that are considered are the various sizes of the stakeholders, the nature of their relationships, and the amount of influence one party has over others. In addition, this can also help a company identify its enemies, and visualize how those organizations might use its influences to move valuable parties in directions that are against one’s interest.[4]

Visualizing these influences can enable Systems Leaders both to prioritize those stakeholders that need to be moved in a particular direction and to see those locations from where positive and negative influences are likely to arise. Plans can thus be enacted to figure out how to engage with particular parties, and the effectiveness of these engagements can be monitored on a regular basis. And critically, this influence map can help Systems Leaders manage the inevitable complexity that comes when markets are undergoing radical and frame-breaking change.

In the context of UCSF, Laret shared that those in his ecosystem include not only interacting with patients and managing their health and positive outcomes, but interacting with physicians, nurses, the state of California, labor unions, insurance companies, philanthropists and others. When asked how he decides how to prioritize which groups with which to interact, Laret highlighted a simple but powerful message — values are the moral compass of a Systems Leader. For Laret, his activities start with an understanding of the moral and ethical levels of what patients need, and then taking actions in those areas that will drive the most impact on these outcomes.

When Laret joined UCSF Health the organization had just come off a failed merger attempt with Stanford Medical Centers. On the surface, this joining of forces would seem to make logical sense — economies of scale would have driven down costs, patients would have had a wider network in which to get services, and two world-class organizations could have combined talents in research and treatments. And, yet, for a variety of reasons (mostly complexity of the ecosystem), the merger was not consummated. Perhaps one of the lessons that we can take away is that the more complex the ecosystem in which one operates, the harder it can be stay focused on customer outcomes and to manage with this objective in mind.

Eighteen years later, with the rise of digital health and the promise of how technologies such as artificial intelligence and personalized medicine can keep people alive longer, the complexity of issues in healthcare continues to grow exponentially. New technologies not only have the potential to ensure that patients are on the right therapies and treatments for their illnesses, but also the challenges with privacy and ensuring that people are not discriminated against by parties in the ecosystem becomes an even greater challenge for Systems Leaders. It is difficult enough to ensure that the newest technologies are providing better patient outcomes; but the complexities of their impact on the various constituents in the healthcare ecosystem creates more challenges for Systems Leaders than ever before.

When to Partner

An additional challenge facing Systems Leaders is that during times of extreme change, those running large organizations need to determine how to work simultaneously with others of various sizes and capabilities. Existing parties will continue to play a role in the industry, and often times smaller new entrants appear on the horizon.

A strategy sometimes used by incumbents is to lever their balance sheets to guide and shape the actions of smaller players via investments or commercial arrangements which create incentives for other organizations to do what the incumbents desire. When done well, these activities, either via corporate venture capital investments or M&A, can be sources of information, new technologies and management talent for a company.

Of course, when done poorly, investment and acquisition activity can distract management from the hard issues that need to be confronted in a rapidly changing world. The most effective corporations use their capital to work with companies that are strategically aligned with the roadmaps of its business units, where other companies get the advantage of the cash a larger firm can provide, and the bigger organization can use the smaller party’s technology or products to further its own strategic objectives. While financial returns are important in such relationships, a strategic operational context is critical for long-term success.

For UCSF, this can be even more challenging than in other corporate venture situations as while new companies may develop technologies and solutions that might have positive impact on patients’ lives, the outcomes are literally matters of life and death. And when the goal is to help people and save lives, Systems Leaders need to be able to tell when they are seeing what they want to see versus what is reality. Laret talked about recent startup failures such as Theranos and others where he had hoped that their solutions would work for the benefit patients, but it turned out that several of the companies he had been tracking went out of business.

Ultimately, large incumbents need to understand if they are committed or just dabbling with their balance sheets. History shows that corporate venture capital rises and falls in unison with the stock market; when the stock market is up, corporate venture activity tends to be high. When the market falls, the “tourists” leave the market and stop participating. A company can only use its balance sheet to help organize an ecosystem if it remains committed to actively participating on an ongoing basis — measured in multiple years or decades.

Finally, a critical challenge for Systems Leaders is to understand not only the influence map of a market, but also where the economic rents are pooled in the value chain. Leaders must be sure that the returns their company is making are commensurate with the risks that the company is taking when interacting with other parties in an ecosystem. For example, in the healthcare industry, direct providers of healthcare are often taking high risks on patient outcomes (which are literally life and death decisions), but, they are usually at the lower-end of the profit pool when compared to others in their industry (e.g. medical equipment makers, pharmaceutical industries, etc.). In such an instance, Systems Leaders need to explore whether their company is receiving an appropriate level of return or not when compared to others, and leadership must understand how they can change or shape the relative ecosystem to their advantage. If they are unable to do so, they must develop a plan on how to get to a better market position by adding appropriate leverage points, or they will never achieve the desired economic targets of their teams or their shareholders for the risks they are undertaking.

As we discussed in class, Laret and his team take the ultimate risks on saving individual’s lives, but healthcare might be the one area where providers such as UCSF have the lowest margins in the healthcare value chain while taking on the most business risk. Systems Leaders not only need to be extremely versatile in managing complex situations, but they also need to understand where they can truly have impact in shaping outcomes for their key constituents. Because of how profit pools have evolved over time in the US healthcare market, perhaps that’s why Laret and his peers must be prolific philanthropic fundraisers — to offset how his organization’s portion of the profit pools does not appropriately align with the risk he and his teammates take.

[1] https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/chart-collection/health-spending-u-s-compare-countries/#item-start

[2] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/ray-noorda-422415.html

[3] Bourne, L., & Walker, D. H. (2005). Visualising and mapping stakeholder influence. Management Decision, 43(5), 649–660.

[4] https://www.quirks.com/articles/mapping-the-chain-of-influence-on-consumer-choice