This XSeed blog was written by Executive-in-Residence, Mike Hoefflinger, and originally appeared on Forbes.

Neither Incrementalism Nor An Infinite Monkey

There’s something special about breakout Silicon Valley-style innovation. Not the ecosystem that makes it possible for hundreds — if not thousands — of efforts to launch, but the handful that win. And keep winning. Big.

Winning — Silicon Valley-style — comes neither from the incrementalism of mega-corporations trying to stay on the innovation treadmill nor the wide-eyed-hope-is-not-a-strategy approach of the over-optimistic entrepreneur. It is, instead, a very rare blend of audacity bordering on arrogance, fearlessness bordering on ignorance and genius that borrows from the nearly 200-year old “go west, young (wo)man” mentality you can still feel here.

The Matrix

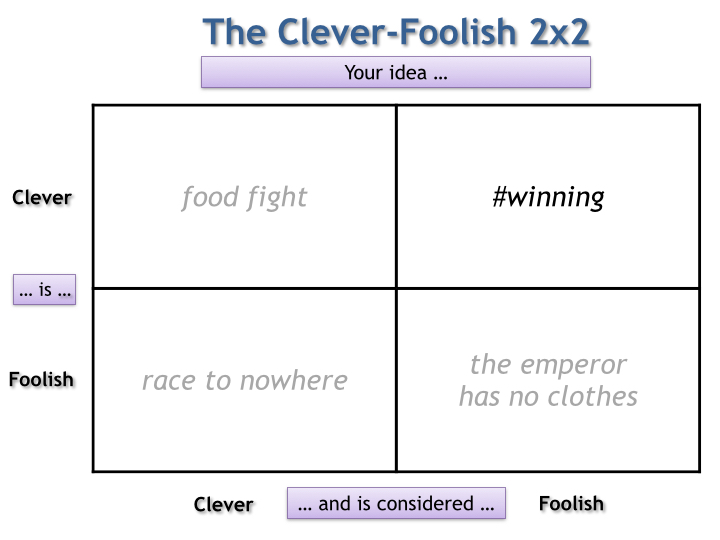

A way to understand this specialness is the “Clever-Foolish 2×2” and its most important quadrant: The very clever idea that’s considered very foolish.

Here’s a look at the quadrants:

Foolish-Clever (“race to nowhere”): Both you and the market think you’re being very clever and consequently competition is fierce. Tragically, time reveals you were not clever and all of you chased each other over the cliff. This is the most dangerously deceptive quadrant, as evidenced by the 2001 Internet bubble (e.g. WebVan, Boo.com, Pets.com). Game over, and boy was that expensive.

Foolish-Foolish (“the emperor has no clothes”): You may think you’ve entered into the market very cleverly (e.g. Tidal), or that you’ve stayed clever (e.g. Blackberry), but the market is leaving you and you can’t see it, admit it, or ideate your way out of it. Game over.

Clever-Clever (“food fight”): So close! You are being clever, but others saw the same opportunity or defended their adjacent turf. The extremely competitive, low-margin environment gives you neither the runway nor the elbow room to differentiate and grab a dominant, sustaining market share (e.g. Gilt, fab.com). Game over.

Clever-Foolish (“#winning”): Congratulations, you are the well-timed, large-scale surprise to the incumbent doubters for whom it’s now too late. Examples include Amazon (vs. bricks-and-mortar in retail), Netflix (vs. Blockbuster in entertainment), Google (vs. Yahoo in search),Facebook (vs. Google in social), Uber (vs. Taxis in personal transportation), Dollar Shave Club (vs. Gillette in direct-to-consumer goods). Now, how to avoid the fate of the ones you displaced?

Knowing (Is) The Difference

Like most strategies, it’s much easier to nod your head about understanding it in hindsight than it is to apply while you’re in the middle of the battle.

How can you know what is clever when everyone around you thinks it’s foolish? You need two very special things:

1. Early internal signals: As big as the above examples are, they all started with small, quick moves which were highly innovative with no proven precursor, but which threw off enough internal data that the companies knew they were onto something before it was evident to everyone else (PS: a famous technology maxim states that while technology moves fast, people move slowly… when you see people moving quickly, pay attention!). Amazon knew from the bell in their garage going off that consumers weren’t nearly as afraid to use their credit cards online as conventional wisdom had it in the mid 90′s. Netflix knew from their DVDs-in-envelopes shipment data that not having to drive to Blockbuster did make a difference. Google could tell from their growing search volume that search had not actually been commoditized in 1999 as competitors believed. Facebook could tell from the rapidity of penetration at college campuses that they were onto something different from both Friendster and MySpace (disclaimer: as a former employee, I still hold shares in Facebook). Uber could see in their data from San Francisco that the ease of use of ordering a black car on demand via your phone trumped the uncertainty of getting in a strange car. Dollar Shave Clubs aw that their early YouTube and Facebook videos and ads were quickly met with consumer demand which agreed that buying razors online is easier, better and cheaper than doing it in-store.

2. A visionary, autocratic founder CEO with the will to act: There is a fine line between audacity and arrogance (“why do you know better than successful companies before you?”), between fearlessness and ignorance (“how will you steer past the complexities that have caused others to fail or that no-one has tackled before?”), and between being successful and just being smart (“do you have the will to lead your company and the industry in the face of the strongest of doubt both behind your back and to your face?”). Leaders of Clever-Foolish companies must be visionary, autocratic, and have the will to act like the CEOs in the examples: Jeff Bezos at Amazon, Reed Hastings at Netflix, Larry Page at Google, Mark Zuckerberg at Facebook, Travis Kalanick at Uber, and Michael Dubin at Dollar Shave Club. Undoubtedly, their management teams, and especially their #2s (most notably Sheryl Sandberg at Facebook, but also the likes of Sundar Pichai at Google) make a big difference, but in the end, the single greatest driver of Clever-Foolish success must be the founder CEO.

As hard as it is to be Clever-Foolish once, it takes multiple instances to be truly great 0r you risk the fate of those you overtook.

Even worse, each successive Clever-Foolish move you make is harder than the last, because the entire market is looking at you more closely after each prior success.

Amazon: Introduced Amazon Prime, which was considered a niche product for the truly e-commerce obsessed, but may have as many as 60M members. Amazon Web Services looked like a puzzling business until it shocked Wall Street with its recent disclosures of scale.

Netflix: As was clear in the company’s name from the very beginning, it was the pivot to streaming that supercharged Netflix, but did so with significant controversy accompanying it as they disrupted themselves. And then they had the guts to pay the big bucks for their own productions (e.g. House of Cards, Orange is the New Black, The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, Daredevil, etc.). Their streaming subscriber base has nearly doubled since then.

Google: Although many looked questioningly at Google’s ability to make a mobile OS happen and at Android’s lack of revenue, Google’s market share lead in mobile OSes can only be considered a piece of brilliant strategic defense of their core search business. Farther down the line will be the fruits of their Advanced Technology and Products (ATAP) andGoogle X labors.

Facebook: Considered lunatic acquisitions at $1B and $19B respectively, Instagram (now 300M+ Monthly Active Users) and WhatsApp (now 800M+ MAU) have been outstanding additions to Zuckerberg’s “make the world more open and connected” family of services. Same with the controversial spin-out of Messenger (700M MAU).

Uber: Although its “I will be driven by an unlicensed driver I don’t know … in their own car” premise is troubling on paper (and is still in conflict with many a regulator), UberX and its 1M drivers has catapulted them to being a transportation giant (possibly a $10B gross run-rate by end of 2015) on the road to being the first “centicorn” since Facebook.

Dollar Shave Club: While a direct-to-consumer internet company may be able to be successful with cheap razors and a great video once (1.7M subscribers at revenue projections of $140M this year say they can), they can’t possibly do it again with expensive line extensions into haircare. Or can they?

Time Changes Everything

Complex as it is to be Clever-Foolish if everything stood still, time plays a complicating role in both the reality and perception of an idea.

What is foolish now may be clever later (related piece at Wired): WebVan lost $800M on the road to being shut down in 2001, but nearly 15 years (and a billion Internet users) later, Amazon Fresh, Instacart and others are alive and well.

What is clever now can decay over time: Being able to receive and send e-mail via a Blackberry was a game changer in the 90′s, but in a post-iPhone world, a smartphone with a physical keyboard and an OS whose name isn’t iOS or Android is no longer competitive.

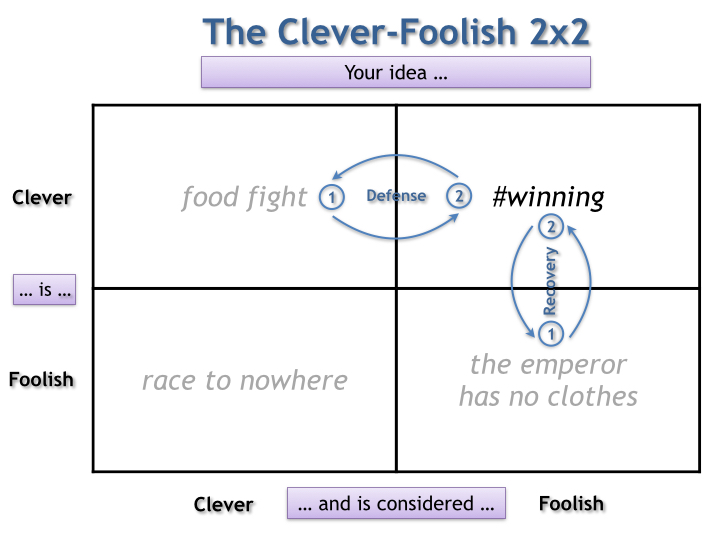

Although you would want to able to celebrate one successful cycle of being Clever-Foolish, both the cleverness of your idea and the cleverness of your competition evolve, giving rise to two kinds of competitive cycles — one where competition realizes how clever you are, and the other where you become foolish:

Defense (Clever-Foolish → Clever-Clever → Clever-Foolish): If you are truly clever, time will eventually betray your secret and you’ll have to once again separate yourself from the food fight. Amazon proving that consumers do love shopping online gave rise to a multitude of curated, niche e-commerce players, including flash sales. Through a superior selection and the perceived-to-be-niche introduction of Amazon Prime, Amazon was once again able to separate themselves from competition.

Recovery (Clever-Foolish → Foolish-Foolish → Clever-Foolish): There’s no better example of losing the plot with a weak product and then regaining it than the progression of Apple under Steve Jobs 1.0 (clever-foolish: the Mac… can high-priced integrated hardware-software experiences really gain large share?) to Apple under Gil Amelio (foolish-foolish: Mac clones) to Apple under Steve Jobs 2.0 (clever-foolish: the iPhone… a new handset in a nearly-commoditized market that demanded carrier exclusives, high subsidies and a share of the related data revenue?).

Who Among You Is Clever-Foolish?

Winning and staying successful Silicon Valley-style is much harder than the mythology would have us believe. The Clever-Foolish 2×2 is the playbook of the best visionary founder CEOs. It can be yours as well.

Where are you (honestly)? Where is your competition? Who is the Clever-Foolish competitor you aren’t thinking about? And where will all of you be two years from now?